How do I understand mental illness as a Christian?

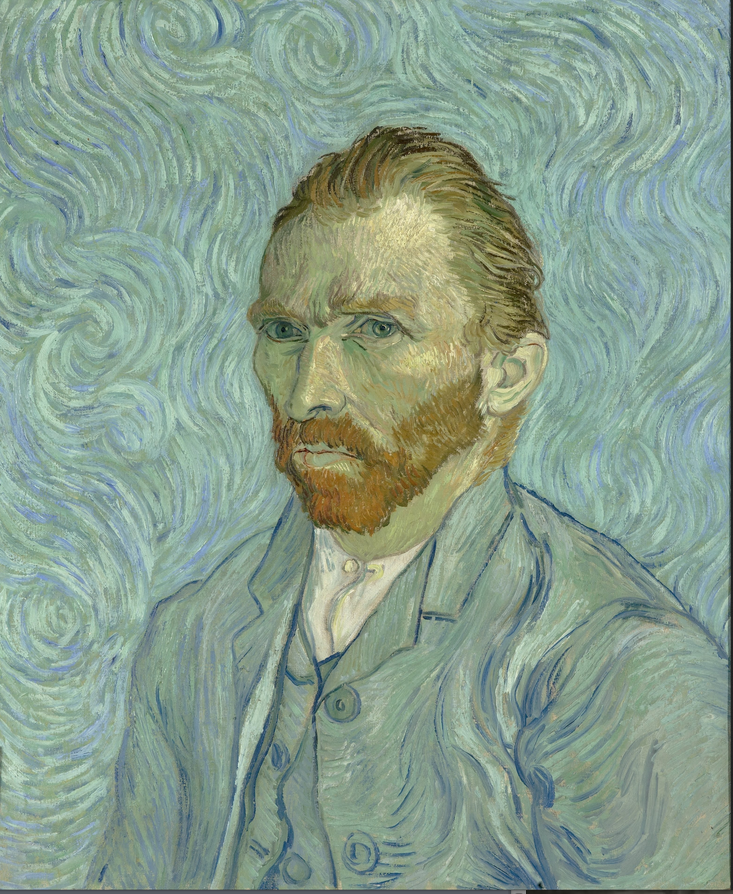

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889, Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris Wiki Commons

To pass the time while doing physical therapy for a broken wrist, I’ve watched a lot of TV. After catching up on The Crown and The Great British Baking Show last fall, I began dropping in on whatever caught my eye. Right now I’m watching The Silk Road, a 2019 documentary by a French journalist. Instead of focusing on the qualities of silk or the exploits of Marco Polo, he follows the geography of the ancient route that brought silk from China to Europe, visiting historic sites and cities from Xi’an to Venice.

In the second episode, I learned something astonishing about a city in western Turkey: Muslims treated the mentally ill with compassion during the Middle Ages. While Westerners were sharpening their witch-hunting skills, the followers of Allah took a much different approach. At a large hospital complex in Edirne (once the capital of the Ottoman Empire), medical care was free to all. This included residential care for the mentally ill and soothing treatments, among them calming music, the sound of water, and aromatherapy. Rose syrup was given as a tonic. The underlying philosophy of this kindness came from Sheikh Ebedeli, who helped shape the policies of the Ottoman Empire during the 1200s. He wrote, “Where human beings flourish, the state will flourish, too.”

THE CHRISTIAN’S DILEMMA

The Islamic world understood more about medicine than Westerners for hundreds of years. While the Ottomans were seeking to relieve mental distress, doctors in the West isolated the mentally ill and even traumatized them with cruel treatments. Too often Western medicine was based on silly ideas and not science. For example, the Doctrine of Signatures stated that God placed a “signature” or sign on plants. If a plant looked like your ailment, it would cure you.

Superstitions aside, Christians face a conundrum when it comes to mental illness. Though we hold firmly to science, we also believe in original sin and personal accountability for one’s life. Since many symptoms of mental illness look strangely similar to personal choice, we suspect a person’s affliction may be caused—at least in part—by their choices. And since we also believe in the existence of angels and evil spirits, we find some symptoms are so bizarre, or so evil, that human agency doesn’t seem a sufficient explanation. Scripture states there are supernatural beings who indwell, afflict, and cause harm to humans.

We’re on our own here. There’s not exactly a heading for free will or demonic activity in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM, its manual of mental disorders. So, we face a dilemma: How do we tell what is brain disease, damage from life experiences, demonic activity, personal choice, or an act of God? When is a person caving in to temptation and when is he a victim? How can we be compassionate but not gullible? How do we help without enabling? What can sanctification reverse or change?

These are difficult, soul-searching, on-your-knees-in-prayer questions. They’re questions I’ve grappled with for the last 20 years as I’ve accompanied my son, now 37, through severe depression. His affliction has bewildered and frightened me. It’s widened the gulf of his skepticism that there could be a loving, personal God.

INADEQUACIES OF SCIENCE

Treating mental illness is done by trial and error, informed by ever-changing theories. If one drug doesn’t work, try another. And too often, psychiatrists focus on altering the brain, leaving the treatment of the “heart” or “mind” to psychologists and others. This biological approach can be maddening, especially when drugs bring a litany of side effects. I’ve watched my son slog through nausea, headaches, and grogginess for months, hanging on long enough to find out if a drug is effective. It rarely is.

To add to the confusion of this inexact science, placebos can be effective. How is that possible? You can relieve depression with a sugar pill? Michael Bernstein and Walter Brown published research in 2018 that proves placebos can cause changes in the brain. They wrote in “The Placebo Effect in Psychiatric Practice”: “Brain imaging technology has revealed that when placebo treatment alleviates pain, Parkinson’s disease, and depression, brain changes occur that are similar to those observed with active pharmacologic treatment.” In other words, the proof’s right there on the screen. The placebo caused a physical change in the brain similar to prescription medications.

A decade ago, Marcia Angell bemoaned the limits of drugs in, “The Illusions of Psychiatry,” in The New York Review of Books. Angell, on the faculty of Harvard Medical School and the former Editor in Chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, wrote of psychiatry’s dependence on the biological model of mental illness. This results in trends, even when it comes to helping kids. “There seem to be fashions in childhood psychiatric diagnoses, with one disorder giving way to the next,” she wrote.

Drug treatment not only follows popular theories, but too many doctors zero in on one symptom while overlooking others. For example, my son hasn’t gotten a good night’s sleep since he was a teenager. Think about how one bad night of sleep can ruin your day. Now multiply that by weeks and months and years. How could you be mentally sound if you’re not sleeping? Shouldn’t that be the first thing addressed?

I respect science. I’ve read as much as possible to educate myself. Neuroscientist David Eagleman explains things in laymen’s terms in his excellent PBS documentary, The Brain, and in his many books. I’ve read dozens of articles and watched documentaries, trying to understand both the brain and that elusive entity scientists call the mind. Daniel Seigel’s 2017 bestseller, The Mind, describes it as a system that shares energy and information with others. In other words, you exist outside of your skull, as a mind in connection with what’s around you.

Brain and mind—what a mystery.

These areas of research focus on physical things. Then there are the many books and articles that address mental illness as a result of trauma, family history, genetics, and personality. It’s overwhelming.

It will be years before we fully understand how the brain works or how to heal mental illness, a quest that has already taken thousands of years. Our modern problems of anxiety, depression, and even schizophrenia are not modern at all. Andrew Scull’s 2015 Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity, delves into the epic struggle faced by cultures all over the world to heal an elusive problem.

MENTAL ILLNESS IN THE BIBLE: GOD, HUMAN CHOICE, TRAUMA, AND DEMONS

Scripture doesn’t shy aware from depicting mental health problems. David writes of his depression and anxiety in the psalms. King Nebuchadnezzar is a narcissist, and King Saul behaves like a schizophrenic. I’ve found four causes of mental health problems in scripture: God, personal choice, trauma, and supernatural beings such as evil spirits or demons. And there are instances where no cause is given.

King Saul’s mental breakdown comes from both God and his own choices. When he flagrantly disobeys God and then lies about it, the Lord withdraws from him. God afflicts him with an evil spirit. As a result, Saul rants and raves and obsesses over his suspicions. He has outbursts of rage. He plots murder.

Saul becomes a tormented soul. He weeps with remorse but cannot change, foreshadowing Paul’s chilling words to the Corinthians of a sorrow that leads to death but not repentance. He intentionally breaks the Mosaic Law to call up the dead. He’s a desperate man who makes reckless decisions. Although an evil spirit afflicts him, his condition is the outcome of his choices.

King David’s daughter, Tamar, is an example of a woman who experienced mental illness because of trauma. What happened to her, as recorded in 2 Samuel 13, is one of the saddest accounts in the Bible. After being raped by her brother, she lived as a “desolate woman” in her brother’s house (2 Samuel 13:20 ESV). Other versions describe her as “a broken woman” (CEB), a “devastated woman” (EHV), or as “always sad and lonely” (CEV). Her mind was traumatized by the devastating experience and there’s no indication she recovered.

In the New Testament, demons are sometimes pinned as causing physical and mental suffering. At times they speak to Christ from inside the person they inhabit (a terrifying prospect). The gospel writer, Mark, records an extraordinary example. A wild man living in a graveyard approaches Jesus. No one can control him, not even with chains and shackles. He has superhuman strength, howls night and day, wanders the mountains, and cuts himself with stones. The gospel of Luke adds a tragic detail: he hasn’t worn clothes “for a long time.” When he encounters Jesus, the demons speak and Christ sends them out. Rescued, the man returns to “his right mind.” He puts on clothes, sits calmly at the feet of Jesus, and begs to join the rabbi’s band of followers.

The gospel writers describe those “oppressed by demons” in the same context as those with physical ailments: paralytics, lepers, the blind, and the dead. They suffer.

COULD ‘DEMONS’ BE SYMBOLIC?

I’ve wondered if “demons” is an ancient expression for faulty wiring in the brain, but scripture clearly states otherwise. People seem to know who is demon possessed and who isn’t. I can’t find a text in which people are huddled in suspicion, trying to figure out what’s going on.

Not all illness is attributed to supernatural interference. For example, John 5 mentions a location in Jerusalem where “a great number of disabled people used to lie—the blind, the lame, the paralyzed.” Nothing spooky going on there. In other texts, demons are blamed for physical or mental sickness. For example, in Matthew 9 Jesus restores the sight of two blind men, and no reason is given for their blindness. Immediately following this story is another healing, this one of a man who can’t speak. In this case the Bible says, “The man was unable to talk because he was possessed by a demon.” So here the author makes it clear that outside forces are at work. So I take God’s word at face value and accept that we have spiritual enemies who can cause affliction.

DO DEVILS MAKE US DO IT?

Life is complicated, isn’t it? When people make moral choices (to lie, to manipulate, to resist correction), it’s hard to believe they’re victims of mental illness. Is this an affliction or is it a choice? Take depression, for example. At what point do our choices to brood over things become habits?

Our thought life is a powerful influence. Paul David Tripp writes in New Morning Mercies: “No one is more influential in your life than you are because no one talks to you more than you do. … We either preach to ourselves a gospel of aloneness, poverty, and inability or the true gospel of God’s presence, power, and constant provision” (February 4).

A family member made an extraordinary recovery from depression a number of years ago. A Christian, she realized that unbelief was at the core of her darkness. (She came to this conclusion on her own—no one forced it on her.) She said her willingness to believe lies (e.g., I’m not good enough, I’m unworthy of being loved, my situation is hopeless) crippled her. She had more faith in those than in Christ. After struggling for years with depression—which also ran in her family for generations—she began preaching to herself the truth of God’s Word. She changed. She went from seeing herself as a victim to embracing God’s narrative about her. She’s been free from depression ever since.

If Satan is the father of lies and his mission is to steal, kill, and destroy, then who stands to benefit from a person crippled by depression and thoughts of suicide? Is it not possible that a spiritual force is at work in their suffering? This is not to say that demonic activity or unbelief is the cause of all mental illness, but only that if doctors struggle to understand the underlying causes, how much more a Christian.

AND YET, WE’RE PHYSICAL CREATURES

I am certainly not suggesting that depression is caused by faulty thinking. I’m simply trying to illustrate how difficult it is to understand the complexities of brain and mind. We know the brain is a body part that can be messed up just like anything else. I’ve sat by my son’s bed in anguish over the firestorm in his mind. His fight against the chaos has been heroic. It’s broken my heart and driven me into despair. Why, God? I have wept and poured out my soul in sorrow over his suffering.

Mental illness is confusing.

WE’RE TRAPPED IN TIME

In a hundred years, we’ll know more about the brain. It’s been said the brain is the final frontier of science. Like Christians in other centuries, we’re caught between the past and the future, between ignorance and knowledge when it comes to medical breakthroughs. One day our clumsy attempts to help people with brain illness will look as archaic as blood letting, a barbaric practice going back to ancient Egypt. Bleeding was a cure-all practiced by the most intelligent doctors at the highest levels of society. You would think something involving leeches would be unpopular, wouldn’t you? How is it possible that its efficacy was unproven, yet it was widely accepted? Our own George Washington did not die from the sore throat he got on a cold, wet day, but because doctors drained forty percent of his blood in less than 24 hours. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that scientists learned blood letting was useless.

Knowing history helps us to hold our opinions lightly when it comes to mental illness. Well meaning Christians have seen demons where none existed, and skeptical Christians have dismissed spiritual interference when they shouldn’t have. We’ve laid guilt on the afflicted, asking if sin is at the core of their troubles.

THREE RESPONSES TO THOSE WHO SUFFER FROM MENTAL ILLNESS

For me, the final answer when faced with the bewilderment of mental illness is threefold.

Show Mercy

Jesus says, “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.” Mercy should be the hallmark of a Christian, but it’s clear from our Lord’s teaching that judgment, not mercy, is our go-to. It’s easy to have mercy when a natural disaster occurs or a friend is in an accident. However, when things aren’t clear, I start asking questions or—even worse—making assumptions. I lean against that tendency by remembering to show compassion first. It’s the most obvious way to obey Christ’s command to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. Mercy changes us, too, as our hearts are opened to the immense suffering and loneliness experienced by the mentally unwell.

Pray

God is more than able to heal anyone, no matter the source of his or her suffering. I plead with him daily to heal my son of his broken mind. He’s a gorgeous, brilliant, and loving man—the kindest person I’ve ever known. He’s creative and funny, and profoundly compassionate. Yet this disease has robbed him of so much, and it would be easy for me to give up hope. “But God,” the Bible says. Christ taught us to pray and keep praying, not letting up or giving up (Luke 18:1). I remind myself of the character of God: Look at who He is! He came up with the idea of a Savior of the World! He is merciful! Lord, hear me and answer my prayer.

Even if the cause is deep trauma, God can heal this as well. Let us ask! As a young Christian, I visited L’Abri in Switzerland where I heard Francis Schaeffer lecture. He was something of a hero to college students in the 1970s; his biblical insights inspired us. Among them was an umbrella term, “substantial healing,” used in his 1971 book, True Spirituality. The idea leans on Paul’s letter to the Romans, which addresses liberation from sin and its effects. Schaeffer taught that the New Testament assumes “substantial” healing in this lifetime from sin’s hold. And so, even in the case of trauma-induced mental illness, such as that experienced by Tamar after being raped, we can pray with hope. We don’t know what God will do—we can’t see the big picture—but that shouldn’t keep us from asking for healing.

How do we pray if a person’s choices cause the mind to descend into mental illness? The example of King Nebuchadnezzar gives us reason to pray for repentance, whole thinking, and rescue. We read in Daniel 4 that after this Babylonian tyrant’s arrogant display of narcissism, God plunged him into a terrible episode of mental illness. The Bible attributes this to his pride and sinful lifestyle, and God humbled him. When his reason returned, he was a changed man, a humbled man. “Now I, Nebuchadnezzar, worship, magnify, and glorify the king of heaven. All his works are truth, all his paths are justice, and he is able to humble all who walk in pride.” (v. 37 CEB) I love that declaration: God is able to humble the proud. And look how good God was to this autocrat, restoring him to his glory.

Finally, there is the question of darkness brought on by demonic forces. This is the most powerful enemy of all: “spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph. 6:12). The practical advice Paul gives for taking a stand against this enemy is clear: pray, stay alert, and equip yourself in gospel truth. As Martin Luther penned in “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” we do not need to tremble in fear though devils threaten to undo us. “One little word” shall fell The Prince of Darkness, and that is the name of Jesus. When I sense spiritual darkness, I pray the light of Christ will interrupt, dispel, and overcome it. “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (John 1:5 NIV)

Extend Genuine Friendship

It’s difficult to remain open to someone whose behavior is erratic or draining, especially those we’re not close to. If we don’t keep our distance physically, we do it emotionally with a “let me help you” attitude. It’s a subtle form of judgment.

Perhaps you’ve had these thoughts: “I don’t want to be bothered with how needy they are. I feel confused. They lie to me. I’m offended by their language. They do weird things.” We see the person through the lens of their illness, not as someone made in the image of God.

We can all agree that we should distance ourselves from a person who means to harm us. We also need strong boundaries because some people will drain the life out of us. That being said, a person with a broken mind needs friendship and respect, to be enjoyed as an image-bearer with unique gifts and talents.

I’ve had to work hard at checking myself in such relationships. A superior attitude creeps in if I don’t pay attention. I ask questions and listen without sharing my life and heart—which protects me from vulnerability. A friend is someone you need, someone you enjoy being with, someone you share life with.

Wherever possible, extend genuine friendship. Enjoy that person. Be open; share your struggles when appropriate. Have coffee together; take a walk. John wrote, “as he is, so are we in this world” (I John 4:7 KJV). I love the TV series, The Chosen, which shows our Jesus as a true friend when he lived among us.

As Jesus is, so are we in this world: showing mercy, praying with hope, and humbly offering genuine friendship.

A FINAL THOUGHT: ONE MAN’S LIFE

I close with Vincent van Gogh for he represents the wonderful gifts that come in broken vessels. (The movie, Loving Vincent, is a beautiful and poignant tribute to a man who continues to be misunderstood.) Van Gogh’s brother, Theo, was devoted to him; he supported his brother throughout their lives. He wasn’t ignorant of Vincent’s faults, and a letter to his sister reveals his practical view of their brother: “It seems as if he were two persons: one, marvelously gifted, tender and refined, the other, egotistic and hard hearted. They present themselves in turns, so that one hears him talk first in one way, then in the other, and always with arguments on both sides. It is a pity that he is his own enemy, for he makes life hard not only for others but also for himself.” Theo loved his brother with full knowledge of his exasperating qualities.

The nature of van Gogh’s mental health issues is still debated today; doctors agree on little more than depression and epilepsy. Of less interest to the secular world is van Gogh’s deeply spiritual life. The son of a Calvinist pastor, he was a devout man. Biographer William Havlicek noted after reading nearly a thousand of van Gogh’s letters that “he loved Jesus; he loved the person Jesus.” A missionary in his younger years, van Gogh turned to art after failure. Burdened with a troubled mind, he created incalculable beauty with his gift, including landscapes that dance and night skies of wonder. Despite the depression and arguments and drinking that swirled around him, at the center—in the eye of the hurricane—there was joy, order, and sensitivity.

What if we trained the eye not to look away but rather to see and acknowledge the gifts of those distressed by mental illness?

In the end, Vincent van Gogh was simply a man, one who struggled to understand God and how to serve others. A man with a mind that betrayed him. Someone like me—like all of us—who needed mercy, prayer, and friendship to share his gifts with the world.